Musings by Linda Cuellar, Ed.D., Community college educator, journalist, video writer and producer who writes and wonders on topics about her life and family, the media, education, border culture, language, travels and U.S. - Mexico issues and topics.

Total Pageviews

Search This Blog

Tuesday, February 19, 2019

Reporting from somewhere over San Antonio

I had just lost my TV news reporting job—Well, to be more precise, I had been fired from my TV reporting job. Publicly fired. Like in- the- newspaper-publicly. I hardly had any savings and my rent was coming up due. I stood in front of my bedroom mirror and wondered just how did I get here? What had happened?

First of all, I’d moved from behind the camera to in front of it— sort of by accident —by necessity, really. I had studied in college to write for TV and Film and to work behind the camera and I did that during college. But later the only jobs I could find in the newsroom, where I wanted to work, were on-the-air. Since I had worked following a bunch of news reporters around, I figured with my Alfred E. Newman reasoning, that if some of the folks I’ve been working with could do News Reporting, so could I. How hard could it be? That’s the kind of girl I’ve always been —take a shot at it. So, I did.

Second of all, and, it’s happened to me once or twice before, things don’t always go as planned. Well in my case, there was this man at work. More precisely, a married man. Ugh. Just know, Yup, it got thick as mud. Even thicker. As thick as Chapapote.

Back to me losing it in front of my bedroom mirror after this brief linguistic aside. “Chapapote” is the word we Laredoans called tar or asphalt. It’s the Aztec word for Tar. The original “hot mess”. These digressions are the blue in the blue cheese. The mint in the mint julep. All the good stuff’s in the digressions. Bit of a cuentista in me. Storyteller. Maybe this tendency gives you a hint at why dry, factual TV news reporting was not working out for me.

Chapapote— Cool word, huh? Did you know you know some Nahuatl too? We can thank the Aztecs for Avocado, which comes from ahuacatl. Also thank the Aztec Nahuatl language for our tomato, guacamole, chili, cacao and best of all..chocolatl, which in Spanish is ’chocolate’, and in English is chopped to be chocolate.

Yay Nahuatl. Still spoken by millions in Mexico. So, not surprising the words had jumped across the river the way all kinds of our border culture jumps back and forth in the borderlands, the way its been since 10 thousand years ago when the Aztecs traded their goods with cultures all through the Great Lakes regions.

You may still want to know more about me and the married man— It was all just a hot, Chapapote mess —there won’t be much more about him. Only to say that once he and his wife became pregnant, I moved 150 miles away to San Antonio.

But let’s go back to Laredo first. I grew up there. In the 60’s, Reader’s Digest magazine, which was a big deal at the time, named Laredo the poorest city in the United States. That wasn’t any news to us. We knew how poor we were. Just look out the window onto our dirt streets. In Laredo, streets were an important topic. Besides the old western song “The Streets of Laredo”, the streets were rutted, caliche dust storms. Any vehicle no matter how slow going raised clouds of fine silt that drifted in doorways and windows and made it into every nook and cranny of our homes. We knew that things were not right. For sure not like the homes and neighborhoods we saw in movies and on TV.

Our mayor and the local political machine that ran the city were big time corrupt. Here’s an example: the mayor’s ranch outside Laredo had paved roads. For miles. Paid for by residents’ taxes. The streets in our neighborhood went unpaved and dusty for years until my mother and our neighbors arranged to pay for our own paving. Then there’s the heat. Our temperatures are so hot that the tar in the asphalt melts— and if you should find yourself walking around barefoot around for some reason, say poverty— the soles of your feet would get all sticky and stained with Chapapote.

As soon as I’d graduated from University, some of us returned to Laredo and worked for the local TV station. I got a job making signs to use in local commercials. My friend, Mark got a job as a cameraman and immediately went out and shot a news story about the sorry state of the streets of Laredo. He set his tripod in the back seat of a news car and filmed roller-coaster, dusty jarring footage of our unpaved streets of Laredo. His footage ran on the news at 6 that night. The mayor phoned the station raising a big fuss and the next day Mark was re-assigned from the news room to production where he got stuck shooting car lot commercials.

After stealing money from us for forty years, the mayor and his minions had become so corrupt that they got careless and got caught. Accounting irregularities in the millions—When the oligarchy finally crumbled, CBS Sixty Minutes came down to South Texas and they ran a segment showing our dummkopf mayor— who we dummkopf residents had kept electing — outright admitting what a crook he was. I didn’t know whether to laugh or cry. Still don’t.

So, fast-forward past the married guy at the Laredo station, and now I’m working in the big city of San Antonio. This was the pre-cable, pre-Internet era, and TV was tops.

It was also the era of appointment television. If you wanted to watch a program, there was no DVR— you had to watch it when it was airing. It’s so different now in the age of streaming. In San Antonio, the station where I had worked had the highest ratings. If the TV was on, people were most likely watching us at 5, 6 and 10.

But now I was out the door and for me the glory was gone. I couldn't call up a city official and say, "Hello, this is Linda Cuellar, News Channel Five calling." All my clout was clouted over. I looked in the mirror and saw that I had to get used to it. At 27, I would soon be too old to get another TV job. No one would recognize me in the supermarket anymore. So, here I was fired. In public. In the paper. No picture with the article thankfully!

There were three of us that were fired —all of us women-- and two weeks later, two men took over our three jobs, sharing the extra salary between them. Three women out. Two men in. You do the math.

Here’s how I much later figured out how it all happened. First, however another brief digression to media history—

Remember this is before the Internet and audiences for the few stations in town were enormous. There was short supply of content and great demand from audiences. In 1980, one of our local anchors made a million dollars a year. For an example of how much smaller audiences are today, consider in 1980 the TV show Dallas had a 34.5 rating. This week's top show NCIS got a 7.5 rating. With limited supply and lots of demand, TV and radio stations operated their extremely lucrative private businesses using something they still use today which belong to the American people, the public airwaves. Internet and Cable don’t use the public airwaves, so they essentially are private businesses. Stations are licensed by the government to use the airwaves through The Federal Communications Commission. The FCC at the time favored stations that complied with affirmative action laws —Those were good days for women and minorities and I was a two-for! I had a university of Texas degree in radio TV film. I was bilingual. But it’s not what helped get me jobs in media. Stations got to check off two columns every time I hired on because I am both a woman and a minority. With the arrival of The new republican president that advantage disappeared. Reagan’s administration pulled the cord on affirmative action in the government and its agencies. Licenses weren’t going to be weighed against who they hired anymore.

That’s how three women were replaced by two men getting the salaries we had been earning.

After I lost my job in tv news I immediately took a news reporter announcer position at a radio station for a lot less money—But, it paid the rent.

Now, I did not make a great deal of money at my old TV job, but I was making even less at this radio job. Plus, I had to work a split shift announcing the news from midnight to 5 a.m. and then I’d go out in the heat of the afternoon to do live radio reports on traffic. I’d drive to the airport and board a clear, plastic bubble about the size of the cab of a small pick up --un-air-conditioned. Inside this roaring heat bubble I sat, cradling a Diet Coke between my knees to keep my tummy from getting nauseous. I’d always had sitting-in-the-backseat- nausea, riding-in-boats-nausea, carnival-ride nausea. Add helicopter nausea to the top of my nausea list. The helicopter pilot was a taciturn guy who had been bumped from doing the traffic reports when I came along. He certainly wasn’t in my corner. He had the not-too-much-confidence-inspiring name of Captain K. He flew us very competently around the reflective, steamy air space hovering over traffic on the winding circular freeways of San Antonio,Texas, average August temperature at 4 p.m. 104.

From inside this baking-in-the-heat whirlybird that roared from take off to landing at noise levels that I can only compare to being front-row center at two side by side heavy metal concerts, I had to monitor three things:

Number one, my Diet Coke. Number two, whatever the DJ at the radio station was playing or saying because every 6 to 8 minutes he would throw it to me to report about rush hour traffic as we flew over all the usual cluster of humanity in cars inching for home below us. I'd do this live, with no script. Not easy for me, the camera-person-turned-news reader to speak off the top of my head. My News Director, who had hired me, liked and encouraged me, but her programming counterpart, the Program Director not so much. I wasn't blonde and bouncy like he liked his women. But I have to admit, sometimes his criticism was justified. Sometimes I stumbled and stammered My rough edges were really showing some days. My Alfred E. Newman, "how hard could it be?" logic was not really working for me. Number three thing I had to monitor: the police radio channel. I had to listen carefully because that's how I learned about car accidents on streets all over town that I needed to warn drivers about avoiding. There were the usual street names like you'd find in any city. Names like Main, Broadway or the numbered ones. We also have streets with all sorts of names going back in the city's 300 year history. Names like Nacadoches, Flores, Alamo, Houston, San Pedro, Culebra, Bandera, Losoya, Durango, Blanco as well as street names that led to ranches like Jones Maltsberger, Callaghan, or Babcock.

The hot days passed one by one and the rent was being paid. My time with Captain K up in the whirlybird doing traffic reporting was getting easier and the program director at the station had stopped yelling at me every single afternoon. So things were looking up.

Then suddenly things took a turn for the worse. A huge truck on the freeway flipped over and dumped a load of asphalt across three lanes causing a massive traffic delay.

Well, I got so excited that day, something newsworthy had finally happened, that I referred to the contents of the truck not by the English terms “asphalt” or “tar” or even the Spanish term “brea” --as in the La Brea Tarpits in California--but by the Aztec term “chapopote" ——I said it just a few times on the air, but when I finished my report my program director went bananas — he screamed at me "Why are you always speaking Spanish on the air?" I answered, "What do you mean? "Chapopote" ? That isn't even Spanish! Do you mean each time I sign off with my name LINDA CUELLAR? Is that what you think I'm doing, speaking Spanish ? It’s my name, dude!!

It would take me a few days to finally catch on, but what the guy at the station yelling at me was saying-- in an indirect manner— because even he knew it was wrong-- was that he wanted to hear me pronounce Spanish street names with an English pronunciation instead of Spanish-- Blank-oh, Floor-es, Dure-ang-oh instead of Blahn-ko, Flo-ress and Du-rahn-goh. Too bad. I was pronouncing all words as well as I was able.

Between flying around like a sun-scorched Peter Pan in the heat above traffic and juggling way more than my upside down tummy could handle, both my time in-the-air and on-the-air was coming to an end. T’his time in a happy landing kind of way. In my usual how hard could it be approach, I applied for a new job, not coincidentally also located at the airport— working as a public relations manager for the airport.

When I got the phone call at home letting me know I’d been selected, I found out I'd beat out a ton of candidates because of my on-air experience and my in-the-air experience flying around in the heat trying to keep it together with Captain K. I rushed back to the mirror in the bedroom and jumped up and down like Mary Tyler Moore in the snow.

And my salary? Twice what it had been in my TV job —plus the newspaper wrote up a nice story about my being hired. And this time with the story about me there was a nice big photograph.

Friday, January 25, 2019

Not My Abuelita,But That's What TV Is For

1962 Nueva Ciudad Guerrero, Tamaullipas, Mexico.

I can imagine my Mexican grandmother, Ventura Molina Flores, so vividly. She was married at 13, had nine children and was fiercely anti-church but a great devotee of the Virgin of Guadalupe. I have a memory from when I was about seven. She stands five feet tall, at her mesquite wood fireplace, cooking our breakfast and uses her bare hands to turn the tortillas she has just made on the blazing hot comal. After breakfast she stands out in her backyard of chickens, pigs, rows of corn and fruit trees watching patiently as my muscle bound teenage brothers try with all their might but fail to cut the mesquite logs for her to use in the fireplace. Nana, which is what we call her, wears her traditional black dress that all widows wore, pale flesh colored cotton stockings and tan cloth shoes that resemble moccasins. She sees the boys have given up chopping and trots out beside the now sweating grandsons and takes the ax. Next, she expertly chip-chips ting-tings at just the right spots upon the logs to chop them to proper fireplace proportions. All our grand kid eyes are bugged out in surprise.

January 24, 2019, Netflix's "One Day At A Time" Episode 13 "Quinces"

"Quinces" is not the way my coming out would have played out with my abuela. She more than likely would have come after me with her ax instead of sewing me a tux for my quinceañera. The Cuban grandmother character played by Rita Moreno struggles in her three inch dancer's heels to climb her own tall mountain of centuries of her culture's homophobia, but she reaches the top. She chooses her granddaughter over convention. Many tears of joy, disbelief, and wonder flowed at my house.

Does this only happen on TV? Does TV reflect cultural change or does it spark the change it first shows? Yes, yes and yes in the case of One Day At a Time producer Norman Lear, who has broken at least as many cultural barriers in his nearly 80 years of working in TV as my grandmother chopped mesquite logs.

God bless all the abuelas as they stand guard protecting their children in the best way they know how.

Wednesday, January 16, 2019

Oh, the good old days of no social media

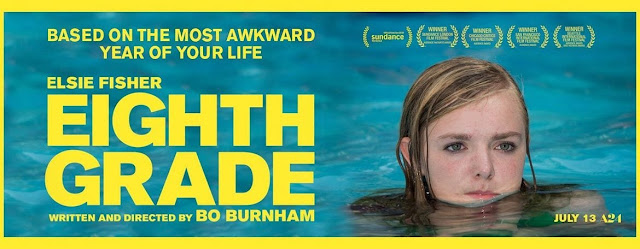

Is anything as heart wrenching as a teenager's mauling and cruel self judgment? Eighth Grade made me step back in time into my moccasins, tee shirt and cut off jeans when my world revolved around (some) my family and (mostly) friends.

1968-69 my eighth grade year ranks as the worst year in my until then much loved and secure life. That fall, I got tossed out of a girls catholic school I'd attended for nine years for exercising my writing and artistic abilities on school bathroom walls. And since my subjects were both innocent and came from powerful families, the nuns showed me the door. I never even got a chance to give my reasons for the graffiti: a full-on war had broken out between two neighborhoods. It was rich versus the poor and the victor (the rich) had taken the spoils: the boys in my old neighborhood had left us girls they had grown up with for new girls who owned swimming pools, and whose maids served sodas to visitors. Was I pissed!!!

The spring semester of eighth grade I enrolled in public school where I knew not one person. My mom and I had to scramble for clothes for me to wear. I had no school clothes, only my old uniforms (bye bye) and play clothes. Add to this the general awkwardness of being 13, the onslaught of puberty, the crushing beauty of everyone around you-- except your own--to which you were blind.

I made it to the end of eighth grade in my new school with some new friends to replace my old gang from catholic school and when the next year began, I flew like an eagle, joining clubs and becoming a junior journalist. I ended the ninth grade semester being awarded more recognition at the school assembly than I thought possible. There was a God and she was two people, my Journalism sponsor, Margarita Newton and my Physical Education coach, Gracie Alderete.

The heavy lifting during this hard time came from me, however. Losing like a cocoon the protective environment of my old school, where I had made merry mischief since kindergarten was harder than I expected. I cringed to think what people said behind my back, but thank God that I had no actual proof or even an idea, because there was no social media to document the gossip and rumors.

Watching Eighth Grade makes me think how much harder it may be to grow up today because of the the additional pressures of images and text to tell you exactly what everyone is writing and saying about you --or not writing and saying.

1968-69 my eighth grade year ranks as the worst year in my until then much loved and secure life. That fall, I got tossed out of a girls catholic school I'd attended for nine years for exercising my writing and artistic abilities on school bathroom walls. And since my subjects were both innocent and came from powerful families, the nuns showed me the door. I never even got a chance to give my reasons for the graffiti: a full-on war had broken out between two neighborhoods. It was rich versus the poor and the victor (the rich) had taken the spoils: the boys in my old neighborhood had left us girls they had grown up with for new girls who owned swimming pools, and whose maids served sodas to visitors. Was I pissed!!!

The spring semester of eighth grade I enrolled in public school where I knew not one person. My mom and I had to scramble for clothes for me to wear. I had no school clothes, only my old uniforms (bye bye) and play clothes. Add to this the general awkwardness of being 13, the onslaught of puberty, the crushing beauty of everyone around you-- except your own--to which you were blind.

I made it to the end of eighth grade in my new school with some new friends to replace my old gang from catholic school and when the next year began, I flew like an eagle, joining clubs and becoming a junior journalist. I ended the ninth grade semester being awarded more recognition at the school assembly than I thought possible. There was a God and she was two people, my Journalism sponsor, Margarita Newton and my Physical Education coach, Gracie Alderete.

The heavy lifting during this hard time came from me, however. Losing like a cocoon the protective environment of my old school, where I had made merry mischief since kindergarten was harder than I expected. I cringed to think what people said behind my back, but thank God that I had no actual proof or even an idea, because there was no social media to document the gossip and rumors.

Watching Eighth Grade makes me think how much harder it may be to grow up today because of the the additional pressures of images and text to tell you exactly what everyone is writing and saying about you --or not writing and saying.

Friday, January 11, 2019

No Patriarchy? No problem.

Today the Los Angeles Times reported on toxic masculinity.

Always the late bloomer, I've just realized that I've lived all of my life, save for the first three years, without a father and thus, outside of the standard, mainstream brand, under-the-nose patriarchy.

My dad died on my third birthday. I'm told I was the light of his life and that I was a very happy baby girl. What his loss meant for me was clear from the start: I missed out immeasurably from his absence. I lacked his approval and affection, his support in all manner of experiences. Perhaps the most important was the hole he left in our family, leaving us without a counterbalance to my mother, left alone to juggle roles of widow, mother of five children. Mama was thrust into a role of leadership that her traditional Mexican culture had sorely under-prepared her for, providing her with sewing instead of school lessons.

What hadn't been clear to me were what advantages came with being brought up fatherless. From my earliest memories, I grew up in a tribe full of brothers, neighbors and uncles, who I studied carefully, learning about their strengths, weaknesses and character. Think of the church and its teachings then add in the mostly manly representations in movies and TV and my heaping plate of male culture was lacking nothing. On the other side of the equation, there were the amazing teachers --all nuns or old-school women teachers that I had until high school. And, back at home, on the main stage, my mother's example, keeping it together for the family despite many, many challenges. My lone and imperfect parent, who for better or worse always knocked herself out for us was my biggest teacher. And she taught me a gal did not need a man to do what needed doing in this world.

1. Go Your Own Way. You may as well follow your bliss. The regular rules do not apply in the absence of a husband and dad. Outside, the patriarchal culture sits like a fog bank safely outside your living room window, but inside, the coast is clear. Keep building the world you want to live in.

2. No patriarchy, no problem. My own agency and accountability served me more than being dependent on approval stamped legitimate by tradition, society or culture.

Tuesday, January 1, 2019

New Year's Painted Night Skies

Fireworks are illegal in the city limits and that is why the Woodlawn Lake Park Rangers quickly patrolled over to any arriving visitors at the park to inform them of the rules. We all know the rules. Following them is another story.

It was an hour before midnight and we strolled with the dog at the dark and empty park to walk off a delicious dinner celebrating decades of friendship. The light fog rose on the streets and under the lamps suspended water particles mixed with fireworks' smoke and debris from hundreds--no, thousands--of yards and driveways surrounding the dark, lonely, law-abiding island. All around on the West Side there were youngsters, hipsters, dudes and dudettes, grandpa's and abuelitas setting off cohetes, fireworks--tradition and sheer fun silencing the law.

Back on our Woodlawn Avenue porch near midnight, the explosions registered in regular rhythm from miles around. At the stroke of midnight the thunder roared without a pause and the light show expanded its panorama. We looked in each direction and the heavens were painted with flying light spectacles rising, exploding and drifting downward. It was hard to hear each other talk or glimpse even a quarter of the night's lighted splendors.

Several cars stopped on the street near us to take in the free light show and sit out the fever-pitch of explosions. Up the street a group of people squatted in between the street and the sidewalk to shoot their contraband fiery missiles and add their flares and explosions to the giant night sky canvas. They, and all of us gazing at our human-made-stars-of-only-a-few-seconds.

My thrifty mother's voice in my head asked, "How much money went up in sparkle and smoke tonight that could have paid for house paint or porch repairs?" Not the point. A better question might be: How many of us need to launch our dreams and hopes for the new year arriving with our own bursting, booming mark on the sky?

Sunday, December 30, 2018

Bruce Springsteen at the Altar of Life

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=M1xDzgob1JI

Bruce Springsteen and I grew up together. We lived and loved in different parts of the country during those same decades that defined us. During the flight across the sky that is our era, we got knocked around in some of the same turbulence, and yet, both of us landed gently enough to look backward with gratitude.

In the tradition of his Irish and Italian ancestors, Springsteen is both a storyteller and a cultural high priest. The kind of priest who is comfortable in a pub filled with hard working hand laborers of all sorts. As he shepherds us through the early years of his life and career, Springsteen confesses to us that he’s never had a job like those who inhabit the working class lives of his songs. He explains he wrote his stories of laborers in the voice of his father, a figure so important to Springsteen that it cannot be overstated. His father, "with the legs and ass of a rhinoceros," held numerous factory jobs when he was well but suffered from depression. It was fascinating to watch Springsteen credit both his parents, two opposites, while giving careful consideration to the resilience and optimism of his mother who informed the artist's lifetime of energy, drive and commitment to his work.

Springsteen's story has taken him around the world several times over only to return to live 10 minutes away from where he started, the town of Freehold, New Jersey. His hometown is a major character in his life: its bars, factories, the neighborhood full of his relatives where he grew up and the giant tree in front of his home that was the center of his life.

I found in the songs and storytelling such love, humanity and a surprising lack of ego for a troubadour who won over the world while staying rooted in his hometown.

The transformation I witnessed as Springsteen presided at his stage and altar, as he took us from his childhood to manhood, surprised me as it corresponded with my own growing up and maturity as a woman of Mexican heritage living in the U.S. I stood beside him as he described, with an Apostle's Creed cadence and the precision of a surgeon, his family's geography and the impact their lives had on him. With each story's turn, I saw reflections of my own story growing up to the same songs, TV and movies 1,911 miles away in South Texas' Laredo. Watching him on his Netflix special, I'll bet I'm not the only Baby Boomer to imagine myself standing behind Springsteen as he performs, not as a backup singer, but as someone who mines the same territories of memory to make sense of family, fortune, loss and perseverance.

Toward the end of the performance, which is based on his Broadway show, I had the same overwhelmed feeling I often get after attending High Mass and standing for more than two hours in an overfilled church. I had been taken on a holy journey. I turned off the TV set and stood up from the sofa exhausted, my thoughts and images still gelling from the immersive music and words that Springsteen performed with fearless grace and candor.

Friday, December 21, 2018

Roma is Alfonso Cuaron's love song to his family and neighborhood in Mexico City.

I was so prepared to dislike Cuaron's entitled family in the film, Roma, but the unflinching honesty of his story-telling made me appreciate the possibilities that can arise after painful rebirth. Think of the many films the child whose story this is grew up to give the world.

Roma is Alfonso Cuaron's love song to his family's neighborhood in Mexico City. It's a stunningly visual film, of course, but its magic also draws from two other sources. The audio track and the many years elapsed since 1971 are as important as the images in this loving but open-eyed inspection of family, class, country and the shifting models of maternity and paternity that this movie shines a light upon.

The music of the era -- Juan Gabriel's classic, "No Tengo Dinero" enters and exits as you glide by street scenes of urban choreography, crowded with street vendors, traffic and pedestrians in purposeful and poetic pandemonium. The frenzy is balanced with thoughtful and carefully mined collections of day to day scenes that paint a detailed portrait of people persevering despite displacement, theft of lands and destructive tremors to supportive structures.

Cuaron re-opens the case against authoritarian abuse with his account of of the killings of hundreds of protesting college students by young men displaced from the countryside, trained by the U.S. CIA, and posing as students.

In Cuaron's middle-class family, the violence is no less. His medical doctor father's decision to leave the household of his wife, her mother, four children and household staff of three (only in post-colonial countries like Mexico with such low wages for domestic workers could this be possible) strikes like an earthquake leaving trembling walls that are no longer reliable.

Upstairs and downstairs residents alike are adrift in this new landscape. The roomy Ford Galaxy the family used before Cuaron's dad's departure gets lodged between two cargo trucks and is smashed into the walls of the family's driveway by Cuaron's mother in a performance that merits its own recognition as metaphor for a marriage's inability to fit where once it did.

The story is a truthful telling of changing roles for mothers and fathers, emerging democracies' efforts (the city that gave us the first university in North America is also the site where at least three times in its history college students would be mowed down by the government) and class as seen through the lives of women who need each other in ways material and spiritual in order to make it through the upheavals of divorce, abandonment and ultimately, making the inner journey with each other's help and understanding, to reach new shores, new beginnings.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)